🍽️ From Public Tables to Fine Dining: How Restaurants Came to Be

- ketogenicfasting

- May 26, 2025

- 27 min read

Updated: Jul 28, 2025

🍽 A Grateful Heart, A Hungry Mind

As I reflect on the long and winding road of culinary history, I’m reminded of the incredible creativity,resourcefulness, and resilience that humans have shown throughout the ages. From open-fire hearths to fermentation pots, from royal banquets to humble street stalls, the journey of food is deeply tied to our survival, joy, and sense of community.

As a chef, I—Chef Janine—feel immense gratitude for the innovations, sacrifices, and traditions handed down by countless cooks, kitchen staff, farmers, and families across centuries. Whether poor or privileged, they all contributed to shaping the world’s diverse and rich culinary heritage.

It’s a blessing to draw inspiration from these enduring legacies, to continue learning, and to build upon the techniques, flavors, and wisdom that have nourished generations. May we carry their spirit forward with respect, curiosity, and love—for the craft, for the culture, and for the people we serve.

Table for Two... A Bite Through Time

From ancient communal meals to modern fine dining, the concept of eating out has evolved remarkably over the centuries. Let's embark on a flavorful journey through time, exploring the milestones that have shaped the restaurant industry as we know it today.

🏛️ 8th to 12th Century B.C. – Thermopolia in Greece and Rome

🍽️Before cafés and takeout joints, there were thermopolia—the ancient Greco-Roman answer to fast food!

Simple, nourishing, and social—thermopolia were more than just eateries. They were neighborhood hubs where hot meals, gossip, and gods came together. 🍷💬🍽️

From the Greek word thermopolion, meaning “place where something hot is sold,” these street-side ready-to-eat food counters kept ancient bellies full. Common among working-class folks in cities like Rome, Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Ostia, thermopolia were a lifeline for those without kitchens—especially residents of cramped insulae apartments. 😋🍷

🧱 Design: Rustic & Practical

A typical thermopolium featured a counter embedded with deep jars (dolia) holding food or drink. Some even had shrines to Mercury (commerce), Bacchus (wine), and the Lares (household gods)—blessing every transaction. 🏛️🍷🛍️

🎨 Art Meets Menu

Walls were painted with eye-catching and appetizing colorful frescoes or covered with mosaics showing what was on offer—🐟 fish, 🍞 bread, 🐓 poultry—functioning like ancient menu billboards.

🏨 Thermopolium of Asellina: Full-Service Flavor

One of Pompeii’s best-preserved thermopolia, Asellina’s shop came complete with dishes, jugs, and even guest rooms upstairs.

Some believe some thermopolia also served as an inn—or possibly a brothel. Upstairs business, downstairs stew? 🤔🍲👀

🦴 Regio V Discovery: 2020 Unearths Ancient Flavor

A newly excavated thermopolium in Pompeii’s Regio V revealed not just food remains and stews, but a painted dog 🐶 reminding customers to leash up, and the skeleton of a very tiny pup—evidence of Roman dog breeding! 🏺🧑🍳🐕

🏺 6th Century B.C. – Ancient Egyptian Eateries🍻

Public taverns—yes, in Ancient Egypt! Dating back to the 6th century B.C., these humble public “eateries” doubled as early public kitchens.

🏠 What Were They?

They were not quite restaurants but informal food hubs usually ran by women 👩🌾. They offered fresh-brewed beer🍺, simple nurishing meals, and a place for the workers, locals, farmers, and weary travelers to gather, rest, and recharge.

No menus. No waitstaff.

But these taverns fulfilled something timeless: Nourishment, comfort, and community. 🌞💛🍺

🍽️ Public Tavern = Beer House🍺

In ancient Egypt, 🍞 bread and beer were sacred staples for all classes. Naturally, this led to the rise of beer houses, which were essentially the same as public taverns. Scholars today use the terms interchangeably.

“Taverns served as food and beer distribution centers,” notes Egyptologist Helen Strudwick. 📚

📜 What was on the Menu?

While exact recipes are lost to time, tomb art and papyri reveal that a simple nourishing dish of cereal, wild fowl, and onions 🥣🦆🧅 were served.

🦆 Wild Fowl

Could include ducks, geese, quail, and pigeons—many of which were wild-caught in the Nile marshlands.

By this period, some birds were also semi-domesticated or farmed.

They were usually seasoned with salt, herbs, or garlic, grilled or stewed.

🌾 Cereal (Grain)

The "cereal" likely referred to one of the following:

Emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccum) – the most common grain in ancient Egypt.

Barley (Hordeum vulgare) – widely used, especially for brewing beer.

🧺 Barley was cultivated and formed the base of most meals, either as:

Porridge or mash

Flatbread

Or thick gruel, sometimes sweetened or flavored with herbs

🧅 Onions

Most likely common onions (Allium cepa) or spring onions.

Both wild and cultivated varieties were known and used.

Onions were daily food for workers and priests.

Onions were also medicinal, and sacred. "Onion" offerings were placed over the eyes of burried mummies!

📜 What Else Was on the Menu?

The flavorful lineup included:

Bread & porridge 🍞

Beer & date wine 🍇🍷

Lentils, garlic, cucumbers 🧄🥒

Fish or meat (for the wealthy) 🐟🍖 🔥

Cooking methods included grilling, baking, and stewing.

🏛️ 2nd Century B.C. – France’s First Roman Tavern

The Lattara Discovery and the Birth of Communal Dining

As we trace the roots of modern restaurants, a remarkable chapter unfolds in southern France. At the ancient site of Lattara near Montpellier, archaeologists from Gettysburg College have unearthed what may be one of the oldest known dining establishments in the region—an early tavern dating back over 2,100 years.

🔥 More Than Bread and Ovens

Initially believed to be a bakery due to the presence of grain mills and large ovens for flatbreads, the site revealed more than daily sustenance. Nearby, a second structure featured benches along the walls and a charcoal-burning hearth at its center—clear signs that this space was meant for people to sit, eat, and share a warm meal.

🍖 Early Hospitality in Roman Gaul

This part of Gaul, conquered by the Romans around 100 B.C., was traditionally home to farming communities. But with the influx of Roman settlers and industry came a need for public dining spaces. “If you’re not growing your own food, where are you going to eat?” noted archaeologist Benjamin Luley. The answer, in true Roman fashion, was practical: build a tavern.

🍷 Wine, Food, and Social Change

In the kitchen area, archaeologists found bones from fish, sheep, and cattle—evidence of varied, protein-rich meals. Yet the most telling finds were fine drinking bowls imported from Italy, hinting at a growing wine culture and a desire for leisurely, communal dining. Far from just a food stop, this tavern was a space of relaxation and social interaction.

📜 A Landmark in Restaurant History

Published findings in Antiquity describe the tavern not only as the first of its kind in the region, but also as a key indicator of how Roman occupation reshaped local economies and daily life. It represents an early shift from private meals to public hospitality—one of the first sparks in the long evolution toward today’s restaurant culture.

🍽️ From Hearth to Haute Cuisine

Lattara’s tavern is a powerful reminder: the desire to gather over a shared meal is ancient, enduring, and foundational to the story of restaurants. Long before menus or maître d’s, people were already carving out spaces to dine, drink, and connect.

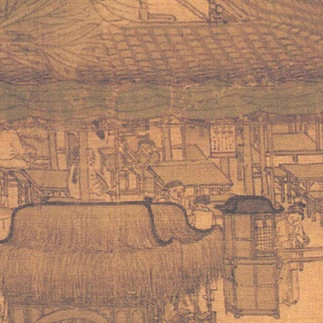

🏮 11th Century – Song Dynasty China's Culinary Scene

In Kaifeng, the capital of China's Song Dynasty, teahouses and restaurants flourished, serving as social hubs for the city's inhabitants.

Kaifeng: Culinary Capital of the Northern Song 🍜🍵

A magnificent 17-foot painted scroll—now preserved in Beijing’s Palace Museum—offers a rare glimpse into the vibrant daily life of Northern Song dynasty Kaifeng.

Rice🍜 and tea🫖 are historically important crops/staple foods in China; but most Chinese during the previous Tang dynasty and before ate wheat🌾 and millet🌾, and drank wine🍷.

Rice🍜 and tea🫖 became dominant food and drink in the Song.

Amid the lively city scenes, what stands out are the bustling teahouses and thriving restaurants. Patrons gather at open-air eateries, shaded terraces, and street-side food stalls, creating a rich tapestry of aromas, flavors, and conversation.

These food establishments weren’t just places to eat—they were cultural centers, where poets, merchants, travelers, and locals mingled over fragrant teas, hot broths, and savory dishes.

🐪Camels from the Silk Road brought spices and ingredients from afar, fueling a dynamic food culture that reflected the city’s cosmopolitan spirit.

🍽️🫖In Kaifeng, dining was more than nourishment—it was a shared urban experience. 🌏

🏰 12th Century – Medieval Europe's Cookshops

🍖🔥 Feasting in the Middle Ages: Europe’s Street Food Scene and More

🍞 Life Before the Fork:

Simple Grains and Sacred Bread

In medieval Europe, food was more than sustenance—it reflected class, culture, and faith.

From the 5th to 15th centuries, 🌾grains like oats, barley, and rye dominated everyday diets, especially among the poor.

Wheat, prized for its role in Christian rituals, was a luxury for the wealthy.

The symbolic role of bread🍞 and wine🍷spread north as Christianity did.

Unlike Islamic dietary laws, which forbade alcohol and pork, European cuisine embraced both—blending religious identity with evolving culinary traditions.

🏘️ 12th Century: Cookshops & On-the-Go Eats

Before takeout, medieval Europe had cookshops—simple street stalls serving hot meals without seating.

City dwellers grabbed quick bites, eating while standing or walking.

Travelers relied on inns, taverns, or monasteries for heartier, communal meals.

Though modest—think stews, bread, and cheese—they offered both nourishment and a welcome rest.

🧂⚖️ Spice and Status: Dining Like Nobility

For medieval nobles, food was a display of wealth and global reach.

Spices like saffron, pepper, and ginger—brought via trade and crusades—transformed meals into sweet-sour delicacies.

Almond milk was a kitchen staple, enriching noble sauces, soups, and stews.

🧀🐟 Meat and Lent-Friendly Fish

Nobles hunted game like venison and boar.

Wealthier peasants raised pigs and poultry.

Beef was rare due to high cost of raising.

In the north, salted cod and pickled herring—preserved by fishmongers—were key, especially during Lent.

🌾 The Medieval Peasant’s Plate

The daily diet of medieval peasants was shaped by class, geography, and the rhythm of the seasons. Socio-economic limitations meant their meals were humble but hearty, built on what was accessible and affordable.

🥣 Foundations of the Diet

Grains like barley, rye, and oats—often made into coarse bread or porridge—formed the core of every meal.

🥕 Legumes and root vegetables such as onions, turnips, and carrots added essential fiber and nutrients.

🍽️ Mealtime Rhythms

Peasants typically ate two to three times a day, often gathering with family or fellow laborers for communal meals. These gatherings were as much about sustenance as they were about connection.

🧀 Sources of Protein

While meat was a rarity, protein came from more modest sources: dairy products, eggs, and on occasion, preserved or hunted meats. Lent-friendly fish, when available, also supplemented the diet.

🌍 Seasonal & Regional Influence

What peasants ate depended heavily on the time of year and local resources. Fresh produce rotated with the seasons, and preservation methods like salting or drying helped carry them through the winter months.

🦠💀 Plague and the Post 1347 Diet

The Black Death (1347–1352) slashed Europe's population—and grain supply. With farmland abandoned, cereals waned while meat consumption rose. Goat, pork, and poultry became staples. Many cookshops closed, but surviving ones adapted, serving more meat-based fare to a leaner, meat-hungry population.

🕌🍷 Faith on the Fork: A Culinary Divide

Medieval food reflected religious lines. Christians embraced pork, wine, and communion bread—symbols that contrasted Islamic dietary laws. Yet, trade thrived, and despite tensions, spices, recipes, and techniques flowed between East and West.

🍽️ In the End: A Feast of Identity

From street cookshops to noble banquets, medieval food reflected class, faith, and culture. More than sustenance, it was a symbol of status, economy, and identity.

🍷 13th Century France: Where Dining Out Began

🍽️ Long before the age of Michelin stars, 13th-century France laid the groundwork for modern dining culture.

In a time when most meals were home-cooked or grabbed from street-side vendors, France’s early eateries offered a new kind of experience—communal, convenient, and, occasionally, a touch refined.

🏨 Inns: Fuel for the Weary Traveler

Rustic and reliable, inns catered to travelers and locals alike. Meals were hearty and no-frills: coarse bread, pungent cheese, sizzling bacon, and spit-roasted meats. Diners sat elbow-to-elbow at long wooden tables, sharing both food and stories by firelight.

🍺 Taverns: A Pot to Share

Taverns brought a bit more structure to medieval dining.

Here, guests could sit and enjoy stews and simple meals, with pricing often set by the pot—perfect for groups or solo eaters.

Drinks flowed freely, and the atmosphere buzzed with gossip, gaming, and occasional song.

🎻 Cabarets: Early Fine Dining?

More upscale than the rest, cabarets introduced a touch of elegance. Tables were draped in cloth, food and wine were served together, and live musicians often entertained the crowd. A cabaret meal wasn’t just dinner—it was an experience, hinting at the future of European dining sophistication.

🍽️ From Function to Flavor

These early French establishments weren’t just about feeding people—they were about gathering, storytelling, and community. Whether refueling at an inn or soaking up ambiance in a cabaret, dining out in 13th-century France was the start of something deliciously enduring.

☕ 16th Century Buzz: The Birth of the Coffeehouse

📍 1555 – The First Café in Constantinople

In 1555, the aroma of roasted beans began to waft through the streets of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), signaling the arrival of a beverage that would reshape social life: coffee. The very first coffeehouse opened its doors here, quickly becoming more than just a place to sip a warm drink—it was a cultural phenomenon in the making.

🗣️ Sip, Talk, Repeat

Unlike the private nature of home meals or religious feasts, the coffeehouse was a public sphere.

Locals gathered to chat, play games, share poetry, and debate politics over tiny cups of thick, rich coffee.

It was a place where ideas flowed as freely as the brew, often called “schools of the wise.”

Locals gathered to chat, play games, sing, share poetry, and debate politics over coffee.

🕌 A New Kind of Gathering Space

Situated at the crossroads of trade and empire, Constantinople’s coffeehouses became hubs of intellectual and civic life.

While taverns in Europe leaned on wine and ale, these venues embraced the clarity and focus of coffee—perfect for long discussions and storytelling.

Religious scholars, merchants, artists, and travelers all found common "ground" in these vibrant meeting spots.

📚 Brewing a New Era

By the mid-16th century, coffee could be found across the Arab world, in North-East Africa and Egypt. The spread of the tradition sped up by the Ottoman conquest of Arabia, first to Constantinople, then to Smyrna, Beirut, and eventually across Europe.

Beyond caffeine, coffeehouses provided access to information. News was exchanged, announcements made, and oral histories passed down. In many ways, they were the precursors to newspapers and cafés as we know them today.

🌍 Legacy in a Cup

The 1555 Constantinople coffeehouse marked the beginning of a global culture of cafés. What started as a simple brew in a bustling city has evolved into a universal ritual—one cup, one conversation, one connection at a time. Yet, coffee has been banned at least five times throughout history. Luckily for us coffee lovers, each and every ban has been unsuccessful.

🍽️ 17th Century – Traiteurs in France

The Original Culinary Craftsmen of France

In pre-revolutionary France, before restaurants became fashionable, traiteurs (from traiter, “to treat”) were the go-to professionals for anyone seeking a refined, prepared meal without hosting a royal kitchen. Before the Michelin star or the maître d’, there was the traiteur—serving sophistication one silver tray at a time.

👑 Dining for the Elite

Traiteurs served the wealthy and aristocratic classes, offering lavish meals cooked offsite and delivered to mansions, salons, and banquets. These were no ordinary cooks—they crafted multi-course feasts featuring terrines, ragouts, sauces, and delicate pastries.

Their work wasn't just about convenience—it was about prestige. Ordering from a traiteur meant you had taste, means, and social standing.

🏛️ A Culinary Turning Point

In the 18th century, traiteurs began offering meals in-house at elegant counters or tables—an early step toward the modern restaurant. Some even posted menus and served multiple customers at once, pioneering a public, semi-private dining model.

🍽️ Legacy on the Plate

Today’s high-end French cuisine owes much to these early culinary entrepreneurs. Their focus on technique, presentation, and service helped shape the DNA of France’s world-renowned dining culture.

🍺 1634 – The Birth of Public Dining in America

Samuel Cole’s Tavern: Boston’s First Taste of Hospitality

Samuel Cole opened the first tavern in Boston, known as Cole's Inn, marking the beginning of public dining in the American colonies.

🍺 A New World, A New Inn

In 1634, just four years after the city of Boston was founded, Samuel Cole opened the doors to Cole’s Inn—the very first public tavern in the American colonies. Nestled near present-day Washington Street, Cole’s Inn wasn’t just a watering hole; it was a cultural cornerstone in a new and growing world.

🍖 Where Ale Met Fellowship

Cole’s Inn quickly became a central hub for Bostonians to gather, eat, and exchange the latest news. The tavern served simple colonial fare like roast meats, stews, and hearty breads—washed down with tankards of ale or cider. But more than that, it offered a place for conversation, deals, and even diplomacy.

From visiting dignitaries to locals in search of warm food and warmer company, Cole’s laid the foundation for public dining as we know it in America.

📜 From Alehouses to America’s Culinary Roots

Long before Yelp reviews or cocktail menus, there was Samuel Cole, serving up colonial comfort and carving out a place in history—one mug at a time.

Cole’s Inn may have vanished in the centuries since (burned down in 1711), but its legacy endures. It marked the start of an American tradition—public spaces where food, community, and culture could come together.

☕ 1650s – England Perks Up

Where Coffee Met Conversation: The Rise of the English Coffeehouse

The first coffeehouse in England opened in Oxford in 1650, followed by London's first in 1652, becoming centers for social and political discourse.

🎓 From Oxford With Buzz

The story of England’s love affair with coffee began in 1650, when the country’s first coffeehouse opened in Oxford. Initially frequented by scholars and students, this new establishment introduced the stimulating brew that would soon fuel minds and ignite debates.

In 1652, London’s first coffeehouse appeared in St. Michael’s Alley, Cornhill, established by Pasqua Rosée under the patronage of Daniel Edwards, a wealthy merchant of the British Levant Company. This venture helped introduce Ottoman coffee culture to British shores.

Footnote: Pasqua Rosée is often hailed as the founder of London’s first coffeehouse, but the full story is likely more complex. Rosée was actually a servant to Daniel Edwards, a wealthy and well-connected merchant with the British Levant Company. Edwards, not Rosée, probably had the means and influence to import Ottoman coffee culture to British shores. While Rosée may have operated the shop, it’s more accurate to see him as a server—while the real credit belongs to the man behind the curtain: Daniel Edwards.

🗞️ Sip, Speak, Stir the Pot

Coffeehouses quickly became hotspots for political chatter, merchant gossip, and literary discussion. Patrons nicknamed them “penny universities”—a nod to the single penny price of a cup and the intellectual riches gained from the discourse inside.

Unlike rowdy taverns, coffeehouses were considered more civilized spaces. They were open to men of all classes who came not just for coffee, but for news, pamphlets, and public debate—laying early groundwork for British journalism and democracy.

🕰️ Brewing a Cultural Shift

By the late 17th century, London boasted over 500 coffeehouses, each with its own crowd—politicians, poets, financiers, and philosophers. Some even evolved into institutions like the London Stock Exchange and Lloyd’s of London.

What started with a humble pour in Oxford transformed English public life, giving rise to modern café culture long before lattes and laptops.

🍵 1672 – Paris's First Café

☕A Sip of the Future

✨In 1672, the scent of something bold and exotic began wafting through the streets of Paris. An Armenian named Pascal operated the city’s very first coffee kiosk, introducing Parisians to the rich, dark allure of coffee. ☕🌍

While the records don’t explicitly confirm that Pasqua Rosée of London and Pascal of Paris are the exact same person, they were very likely part of the same movement of Levantine coffee pioneers — and possibly the same man helping Daniel Edwards of British Levant Company expand his coffee vision across borders.

Some sources suggest that Pasqua Rosée of London later moved from London to Paris and helped spark the trend there. The 1672 Parisian coffee kiosk by “Pascal the Armenian” is widely believed to be the French extension or echo of that same wave of early coffee culture spread by Ottomans in Europe.

Regardless whether Pascal was the same person in both cities, at a time when inns, taverns and cabarets dominated social life, the new café establishment offered something new: a space for conversation, contemplation, and caffeine. 🗣️💭☕ More than just a drink, coffee gradually became a cultural phenomenon—fueling thinkers, artists, and revolutionaries. 🧠🎨⚡

Footnote: Pasqua Rosée (or Pascal), often credited with founding the first coffeehouses in both London (1652) and Paris (1672), was in fact a servant of Daniel Edwards, a wealthy and well-connected merchant of the British Levant Company. Edwards, not Rosée, held the financial means, trade access, and legal authority to import and distribute coffee within Europe. It is far more plausible that Edwards orchestrated the early coffee ventures, with Rosée or Pascal acting as the server or operator. The romanticized elevation of a servant to “founder” reflects a simplified and mythologized version of events, obscuring the imperial trade structures and power dynamics at play.

🥐 From Coffee to Croissants

In the years that followed, cafés evolved into cozy hubs that didn’t just serve coffee—but also fresh-baked delights. Breads, tarts, and the now-iconic croissant became staples of café menus, giving rise to France’s beloved café-boulangerie (café-bakery) culture. ☕+🥐 = ❤️

Today, sipping an espresso with a warm pastry in a sunlit Paris café is more than a meal—it’s a ritual.🪟🍰

The widespread café culture in Paris developed over the ensuing decades, with establishments like Café Procope, opened in 1686, becoming popular meeting places for intellectuals and artists.

☕🥐 From Foreign Treats to French Tradition: How Coffee and Croissants Became a Morning Ritual

The combination of croissants and coffee as a typical Parisian breakfast likely became commonplace in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as both items became more accessible and ingrained in French culinary habits.

The evolution of this pairing reflects broader social and economic changes, including the rise of café culture and the adaptation of foreign culinary influences into French cuisine.

📜 Was the term “café” already coined in 1650s?

The word “café” (from the French word for coffee, which itself comes from the Turkish kahve and Arabic qahwa) began to be used around that time in France. The term quickly came to refer not just to the beverage, but also to the type of establishment where it was served.

While the Coffee kiosk Pascal operated may not have called a “café”, the term did emerge shortly afterward and became common as these establishments grew in popularity through the late 17th and 18th centuries.

☕✨ By the early 1700s, "café" was firmly established in French vocabulary and culture.

☕ 1683 – How Vienna Got Its Buzz: Coffee, Cannons, and Storytelling

One of the most popular legends surrounding the introduction of coffee to Vienna is mostly myth with a kernel of truth.

☕ The Legend:

During the 1683 Siege of Vienna, the city was under attack by Ottoman forces. When the Ottomans retreated, they allegedly left behind sacks of mysterious beans. A Viennese man named Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki supposedly recognized them as coffee, having learned about it while in Ottoman lands. He then opened Vienna's first coffeehouse using the abandoned supply.

Some even add that the beans were burning or smoldering, producing an unusual aroma that attracted attention—thus sparking Vienna’s coffeehouse tradition.

🧐 The Truth:

The Ottomans did retreat and did leave supplies behind, but there is no concrete historical evidence that coffee was among the abandoned items.

Jerzy Kulczycki did indeed open one of the first coffeehouses, and he played a notable role in popularizing coffee in Vienna.

However, the story about burning beans and coffee sacks being mistaken for camel feed is almost certainly a romanticized tale invented much later.

Historical records show that coffee was already known in Europe by the early 17th century, decades before the siege, especially through trade with Venice.

🥐 1683 – Myths, Moon-Shapes & Morning Glory

The Croissant’s Legendary Origins

The popular tale that the croissant was invented in Vienna to celebrate the defeat of the Ottoman Empire is charming—but largely a myth.

🥐 The Legend:

One of the most delicious legends in food lore ties the invention of the croissant to the Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1683. As the story goes, Viennese bakers, working through the night, heard the Turks tunneling under the city and raised the alarm. When the siege was repelled, the bakers allegedly created a pastry shaped like the crescent moon—the symbol on the Ottoman flag—as a sweet celebration of victory.

📜 The Facts:

Though charming, historians view this tale as more myth than fact.

The idea likely originated from the 13th century Austrian “kipferl,” a crescent-shaped bread.

The kipferl reached France in the 1830s when August Zang opened his Viennese bakery in Paris.

French bakers adapted kipferl into the modern croissant—a flaky, buttery, laminated pastry—using puff pastry techniques.

🍽️ Bottom Line:

While the siege legend makes for a fun story, the croissant’s true origins are more culinary evolution than wartime celebration—with roots in Austria, but its buttery glory perfected in France. Still, the legend lives on—because what’s breakfast without a good story?

🥣 1765 – A Bowl of Broth That Changed Everything

🍲 The Birth of the “Restaurant”

🥣 In 1765, a Parisian named Boulanger opened a small establishment selling bouillons restauratifs—“restorative broths”—meant to rejuvenate weary patrons. At the time, food was mostly served by inns, taverns, or guild-licensed caterers.

But, Boulanger’s shop was different: it focused on individual nourishment, not communal meals or heavy fare.

🪧 A New Kind of Eatery

Above his door, Boulanger posted a bold Latin phrase: “Venite ad me omnes qui stomacho laboratis et ego restaurabo vos” — “Come to me, all who suffer from the stomach, and I will restore you.” It was both marketing and a mission. His innovative idea gave birth to the term restaurant—from restaurer, meaning "to restore."

A Quiet Culinary Revolution

Boulanger’s little broth shop quietly sparked a dining revolution. By the late 18th century, restaurants became fashionable in Paris, offering patrons menus, private tables, and made-to-order meals. The humble bowl of soup had become the seed of modern dining as we know it. Read more on this topic: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/who-invented-the-first-modern-restaurant

🍽️ 1782 – La Grande Taverne de Londres

Fine Dining Takes Form in Paris

👨🍳 Beauvilliers and the Birth of the Modern Restaurant

In 1782, Antoine Beauvilliers, a former chef to French nobility, opened La Grande Taverne de Londres in Paris. This wasn’t just another eatery—it was a refined dining experience that set new standards in hospitality. With individual tables, uniformed waiters, and a carefully curated menu, Beauvilliers brought elegance and order to public dining.

📜 Menus, Manners, and Mastery

Unlike taverns or inns, his restaurant featured an extensive à la carte menu, allowing guests to select dishes as they pleased—a novelty at the time. Dishes were refined, service was polished, and ambiance was upscale. It wasn’t just about eating—it was about dining.

La Grande Taverne de Londres is no longer in operation. The establishment closed its doors in 1825, a few years after Beauvilliers' death in 1817.

A Lasting Legacy

Beauvilliers helped define what we now recognize as the modern French restaurant. His innovations—private tables, printed menus, attentive service—laid the foundation for the fine dining culture that would soon sweep across Europe and beyond.

Beauvilliers, later wrote L’Art du cuisinier (1814), a cookbook that became a standard work on French culinary art.

1794 – Julien's Restorator in Boston

A Taste of France in the New World

👨🍳 From revolution to restoration, French refugee Jean-Baptiste Gilbert Paypalt Julien served not just food, but introduced the restaurant concept to the United States and with that, changed the future of American dining.

🍲 Refugee to Restaurateur

In 1793, French refugee Jean-Baptiste Gilbert Paypalt brought more than his passport to Boston—he brought an idea that would transform American dining. Fleeing the chaos of the French Revolution, Paypalt opened Julien’s Restorator, one of the earliest restaurants in the United States.

🍽️ From Broth to Business

The term "restorator" came from restoratif, meaning something that restores strength—typically a nourishing broth. Julien’s Restorator offered comforting soups, along with carefully prepared meals, individual tables, and an emphasis on health and refinement—radically different from the loud, ale-soaked taverns common at the time.

🧾 A New Dining Model

Julien’s menu reflected his French roots and elevated the expectations of American diners. It was clean, respectable, and organized—an ideal setting for gentlemen and fine ladies alike. His innovation helped lay the foundation for the full-service, sit-down restaurant culture in the U.S.

🥖 A Lasting Influence

Though Julien’s Restorator closed in the early 1800s, its legacy endures. Paypalt’s elegant European concept proved that Americans had an appetite for more than just tavern fare—they were ready to dine.

🥩 1827 – Delmonico's in New York City

🍽️ Delmonico’s: The Birth of American Fine Dining

Delmonico's began as a pastry shop and evolved into America's first fine dining restaurant, known for its luxurious offerings and influential patrons. ✨ From pastries to presidents, Delmonico’s served up a new American dream—one elegant course at a time.

🥩 Delmonico’s Returns: A Culinary Icon Reopened

In 1923, the legendary Delmonico’s closed due to Prohibition, but was revived in 1926 by Tuscan immigrant Oscar Tucci, who preserved and elevated its legacy.

After shuttering in 2020 due to the pandemic, Delmonico’s reopened its doors on September 15, 2023, at its historic Beaver Street location in NYC.

Following legal disputes and a major renovation, new operators Dennis Turcinovic and Joseph Licul, joined by Max Tucci (grandson of former owner Oscar Tucci), revived the famed steakhouse with a fresh yet faithful vision.

Now open for lunch and dinner, Delmonico’s offers timeless favorites like the Delmonico Steak and Baked Alaska, alongside modern dishes by Executive Chef Edward J. Hong.

🥩 Legacy on the Plate

Delmonico’s transformed dining into an art form. The restaurant gave rise to signature dishes like Lobster Newberg, Baked Alaska, and the legendary Delmonico Steak. These iconic dishes still grace menus across America today. They helped define what Americans would come to expect from fine dining.

🍰 From Pastry to Prestige

Rooted in the heart of old New York, the Swiss immigrant Delmonico brothers Giovanni and Pietro established Delmonico’s in 1827, first as a humble confectionery. But this was no ordinary confectionery shop—it was the seed of what would become Delmonico’s, America’s first fine dining restaurant.

🥂 Setting the Standard

By the 1830s, Delmonico’s had evolved into a grand establishment offering white tablecloth service, an à la carte menu, and private dining rooms—luxuries unheard of in American eateries at the time. The restaurant dazzled diners with French-inspired cuisine, fine wines, and impeccable service. By 1837, they opened the restaurant extension of Delmonico's, creating what became known as America’s first fine dining restaurant. The brothers set new standards with white tablecloth service, à la carte menus, and an atmosphere of refined elegance.

👑 A Table for the Elite

Delmonico’s quickly became world-renowned. Presidents, authors, tycoons, and artists filled its dining rooms—Mark Twain, Charles Dickens, and Abraham Lincoln among its celebrated guests. It wasn't just about the food; it was the place to be seen, it was a full cultural experience.

🏛️ More Than a Meal

Delmonico’s transformed how Americans experienced food—turning dining into a refined, cultural event. Nearly two centuries later, Delmonico’s remains a symbol of American fine dining, known for its pioneering cuisine, iconic guests, and enduring commitment to hospitality and tradition. Its legacy lives on as the blueprint for luxury restaurants across the country.

🍻 1860s – Bistros and Brasseries in France

🥖 The Soul of French Street Dining

These smaller establishments offered moderately priced food and drinks, catering to a broader clientele and becoming staples of French dining culture.

🥖 Casual Meets Comfort

In 1860s France, the bustling energy of urban life gave rise to a new kind of eatery: the bistro and the brasserie. Unlike the grand, formal restaurants that catered to the elite, these cozy establishments embraced simplicity and warmth. Bistros offered modestly priced, home-style meals—think stews, roast chicken, and rustic bread—perfect for the working class or anyone seeking a hearty, affordable dish.

🍺 From Breweries to Brasseries

Brasseries, originally tied to breweries, expanded on the bistro concept with beer on tap, longer hours, and a slightly more refined menu. These spots became popular gathering places, where one could enjoy a croque monsieur or steak frites without breaking the bank.

👥 Dining for the People

More than just places to eat, bistros and brasseries became central to French social life. They welcomed artists, students, and everyday folks alike—offering not only food, but community. Their rise marked a democratization of dining, bridging the gap between street food and haute cuisine.

A Lasting Legacy

Today, bistros and brasseries remain beloved fixtures in France and beyond. Their enduring charm lies in their unpretentious spirit—good food, good drink, and good company.

🍷🥐 “Bistro or Brasserie?”—Let’s Wine Down the Difference

While bistros and brasseries are often lumped together, they actually have distinct differences rooted in French culinary culture. Here's a quick breakdown:

🥖 Bistro

Origin: From the Russian word "bystro" (meaning "quick")—possibly shouted by Russian soldiers in Paris during the early 19th century.

Vibe: Small, casual, cozy neighborhood spot.

Food: Simple, hearty home-style meals—think beef bourguignon, coq au vin, omelets.

Hours: Limited; typically lunch and dinner.

Drinks: Modest wine or house wine selections.

Menu: Short, seasonal, and often written on a chalkboard.

🍺 Brasserie

Origin: French for “brewery”; initially places that brewed and served their own beer.

Vibe: Larger, busier, more upscale than a bistro.

Food: Traditional French fare but with a broader, more consistent menu—oysters, steak frites, seafood platters.

Hours: Open all day; often with continuous service.

Drinks: Wider beverage offerings, including beer, wine, and aperitifs.

Menu: Printed, fixed, and more extensive than a bistro’s.

In short:

A bistro is intimate and homey 🍲, ideal for a quiet, rustic meal.

A brasserie is lively and polished 🍾, perfect for dining at any hour with a full menu and drinks.

Both are essential threads in the fabric of French culinary tradition.

🚂 Late 19th Century – Dining on the Move

All Aboard for a Taste of Luxury

With the expansion of railways, dining cars and station restaurants emerged, making quality meals accessible to travelers. From steam to soufflé, the railway brought people—and plates—together in motion.

🍽️ Meals with a View

As railroads carved their way across continents, they didn’t just carry passengers—they revolutionized how people dined.

In the late 1800s, the introduction of dining cars transformed the travel experience. No longer did hungry travelers need to pack dry snacks or rely on unpredictable station vendors.

🏢 Station Stops Turned Gourmet

Major railway stations soon boasted elegant station restaurants, offering warm meals and stylish interiors that rivaled fine dining spots in the city.

These culinary hubs catered to both hurried commuters and leisurely explorers seeking a sit-down meal mid-journey.

🥂 Classy and Connected

Dining cars became symbols of sophistication, with white tablecloths, silver service, and menus featuring roast meats, fresh vegetables, and even champagne. For many, it was their first taste of restaurant-quality food—on wheels!

🌍 A New Era of Eating Out

This era marked a shift: eating out was no longer limited to the urban elite. Travel and dining merged, and food became an essential part of the journey—not just the destination.

🍔 20th Century – The Rise of Fast Food

Drive-Thru Dreams & a Diet Dilemma

Post-World War II America saw the emergence of fast-food chains like McDonald's and Kentucky Fried Chicken, revolutionizing the dining experience.

🚗 Speed Meets the American Appetite

Post–World War II America was hungry for convenience.A booming economy, the rise of car culture, and the growth of suburban life created the perfect storm for a new culinary era: no reservations, no waiting—just quick bites on the go.

Amid these sweeping social and economic shifts, fast food chains like McDonald’s and KFC found fertile ground for rapid expansion. Their quick, affordable meals redefined American dining—transforming the once-special occasion of eating out into an everyday ritual.

🌍 Global Flavor, Local Price

Fast food chains spread like wildfire, first across the U.S., then the globe. Their low prices, catchy jingles, and consistent menus turned them into cultural icons—bringing burgers, fried chicken, and milkshakes to every corner of the world.

🍟 Birth of the Giants

In the 1950s, McDonald’s introduced its streamlined service model, serving burgers and fries at lightning speed.

Around the same time, Colonel Sanders was perfecting his secret recipe, giving birth to Kentucky Fried Chicken.

These weren’t just meals—they were movements. From carhops to combo meals, the rise of fast food redefined how—and how often—Americans and world youth eat out.

🍟 From Innovation to Industrialization → Fast Food Took a Dark Turn⚠️

💰 As the industry grew, speed and profit trumped quality.

🍟 Once golden fries cooked in wholesome beef tallow or lard → now deep-fried in inflammatory seed oils. 😠

🥩 Meats are now pumped with hormones and antibiotics to grow faster, not better. 😡

🥕 Vegetables? Genetically modified and stripped of nutrients. 😤

🍞 Buns—once hearty and nutritious—now made from GMO grains, highly refined to remove:

❌ Fiber

❌ Vitamins

❌ Minerals👉 Leaving just empty starch (aka: sugar bombs). 😠

🥤 Soft drinks became chemical cocktails:

Loaded with petroleum-based dyes 🎨

Aspartame and high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS)

👀 Sweetened to mask the metabolic damage

📦 Wrapped in Trouble

It didn’t stop at the ingredients. Packaging is often laced with phthalates, known hormone disruptors. The very materials meant to “conveniently” carry our food are now contributing to the chronic illness epidemic. The result? A nation fed—but not nourished.

⚠️ A Wake-Up Call

Today, millions of Americans suffer from diet-related chronic diseases—many unaware of the root cause. Worse yet, in many areas, fast food is the only affordable option, leaving families trapped in a vicious cycle of illness and addiction.

🗳️ Time for Change

A growing number of citizens are demanding better. As election cycles heat up, there’s rising public expectation that MAHA, RFK Jr., and the Trump administration will address this crisis—reining in Big Food’s reckless practices and restoring integrity to America’s plate.

The counter-revolution might just start at the drive-thru. 🍽️

🌮 1960s-70s – Diversification of Dining

🍽️ From Sit-Down to Sell-Out: The Chain Reaction

The restaurant industry expanded with the introduction of various chains like Taco Bell, T.G.I. Friday's, and Red Lobster, offering diverse cuisines to the masses. What began as novel and accessible dining soon turned into a sprawling, profit-driven machine.

💸 While offering convenience and consistency, many of these chains now follow the same path as the fast food industry—prioritizing cost-cutting and mass production over health and nutrition. From ingredient sourcing to preparation techniques, they rely on the same industrial food systems:

🧪 Ultra-processed, nutrient-poor ingredients

🐄 Hormone- and antibiotic-laced meats

🌽 GMO and fiber-stripped grains

🍟 Seed oils replacing wholesome animal fats

🧃 Artificial sweeteners, colorings, and preservatives

These choices aren't made with the consumer’s wellness in mind—they're made for shareholder returns. And the consequences are showing: a population plagued by chronic illness, with few healthy options in sight.

In Closing...

From humble beginnings to global franchises, the restaurant industry continues to evolve—but not always in the direction of health or integrity. It's time for conscious eaters and ethical leaders to demand better.